When WW2 was winding down, I served on a ship converted to carry Australian war brides and their children to be re-united with their husbands.

After leaving Aden Yemen, we were about half way across the Indian ocean when problems started to manifest themselves. At first, it appeared to be just an isolated incident. Bad things always seem to happen during a most vulnerable period, and with small ships it was in mid ocean, with practically no possibility of getting help on short notice, and with very few facilities.

There were quite a few babies on board, all over six months old, which was the minimum age regulation required before allowing them to travel by sea. Just a handful, about four or five were very close to that age, and I had seen them battle through seasickness as they travelled through the consistently choppy Bay of Biscay after leaving England. On this day however, one of them, a baby girl fell sick, and as usual, word got around in a very short time.

There was a doctor on board, and two nurses were travelling in a dual role of passengers and making themselves available should they be required, so for all intents and purposes, medical assistance was there twenty-four hours a day.

The following morning around 11.30 am, I walked along the passenger deck on my way to do the 12 noon to 4 p.m. watch, when I noticed a young mother sitting under the mid ship companion way. She had placed the baby in her bassinet out of the wind and I decided that it would be alright under the circumstances to break the fraternization rule, and go over to speak to her.

She was in her early twenties, small, thin, and frail looking, her face showing signs of strain. “How is your baby today?” I asked, but the woman’s response was hardly perceptible, her eyes never moving away from the bassinette. I looked inside, but just at that precise moment was interrupted by a voice calling from the upper deck above me.

“Is that you Will Bonner?” It was the bosun’s mate, Glen Douglas. “Would you report to the doctor’s cabin, he is waiting for you.”

I made my way up to the officers' quarters and knocked on the doctor’s door.

Doctor Frank Carlisle was an old man, over seventy years of age. Previously serving with the British armed forces in India. He stood around 6ft 6in. tall and I had often seen him constantly bending his head as he negotiated the doorways.

His peaked white cap made him look even taller as he stood at the end of his solid looking desk. His bony, rugged face, was never without a black cigarette holder protruding from his mouth, which he only removed when preparing to speak. His bearing was that of quiet authority, an attribute that I respected. “Sit down Bonner,” he said, pointing to a chair.

I sat down; my mind filled with apprehension. I could not think of a single thing that would warrant this meeting. The doctor raised his big bushy eyebrows after clumsily maneuvering his bony into the seating position behind his desk.

I moved uneasily in my seat. I wish he would get on with it I thought, as further moments slipped by. The doctor took a deep draw on his cigarette and turned his head slightly to blow the smoke at an angle over his right shoulder. “You no doubt know Bonner that there are sick babies aboard?”

“Yes doctor, but I fail to see…The doctor broke into my conversation.

“You’re a technical type, aren’t you?”

“Yes doctor, but what bearing…?” My answer was again cut short.

“I have no assistant aboard and I need someone with a logical mind that can act on instruction and you fit the requirements. Your duties can be taken over temporarily.”

I was determined this time not to be cut off, “But I have no experience in medical matters, and you have two nurses on board.”

“Yes, but I can only request their services when an emergency arises. In the meantime, I need someone that I can allot certain tasks under my guidance.” He hesitated and then continued. “I know that you can do the job, but I cannot order you to do it. There is no promotion involved - it’s just a one-off situation, what do you think?”

I was aware that the doctor was scrutinizing my reaction and I was struggling to come up with an excuse to extradite myself from this sudden turn of events, but nothing came. I heard myself saying, “Alright, I’ll give it a go doctor, when do I start?”

“We’ll go down to the dispensary right now and I'll show you what I want done.”

Picking up his medical bag, they left the cabin and made their way along the passenger deck.

The two nurses were waiting at the dispensary door and the doctor introduced me, outlining what my duties would be. The younger of the two nodded, but the older woman showed no reaction. As the door opened, I smelt the pungent odor of medicine. I had never had the occasion to go there before and looked in amazement at the size of the room. Obviously designed for the doctor and one patient only, a third person would be a tight squeeze, a fourth impossible.

I stayed out in the alleyway with the younger nurse as the older woman and the doctor entered the dispensary and could not help overhearing the words as she conversed with the doctor. “Two more babies have fallen sick.”

“Are they showing the same symptoms?

“Yes, just in the early stages,” and she then proceeded to give the names and cabin numbers of the sick babies.

“I’ll go up there when I've finished here.”

I could only think the worst. After the nurses had gone, I talked with the doctor for a while, and he left me with the keys to the dispensary, but not the drug cabinets. I unlocked the door at the end of the short alleyway which gave access to the ship’s hospital.

It was small, just four beds. The whole setting painted a very basic picture. Except for the dark grey blankets on the beds, every aspect of the room was steel and more steel. Sounds echoed with the emptiness.

I closed the door behind me hoping that he, or anyone else for that matter, would not fall sick and have to be incarcerated there. Unless I was called upon in the meantime, my next duty would be to attend the dispensary early that evening, and then the following morning. My stomach turned at the thought of what I could expect from some members of the crew when they appeared for treatment.

I walked up to the passenger deck. For me the fraternization rule was no longer applicable, and the women would eventually get to know that they could use me as a go-between to get to the doctor. I could not see the nurses, they were probably with the women whose babies had just fallen ill, so I just wandered the deck, getting the occasional hesitant nod. Settling into my new set of circumstances would not be easy.

Deciding to make one more circuit of the deck before going up to see my superior and talk about the change, I was about to leave the deck, when I caught sight of the young woman whose name, I now knew to be Doreen Bradshaw.

She was lowering herself into a deckchair next to the bassinet and had obviously only just arrived on deck. Asking about the baby brought a weak smile, and interpreted the response as probable good news. I was therefore, totally unprepared for what confronted me, when I leaned over and looked into the bassinette I was.shocked.

I could not come to terms with what I had seen, my mind temporarily blacked out in disbelief. Concentrating totally on the baby’s face I could see no sign of movement, and I froze once again trying desperately to eliminate the thoughts that were constantly surfacing. Now more aware of the mother’s presence, I tried to calm myself.

Looking frantically along the deck I could see no one that I could ask for assistance, and had no other option but to move away slowly in an effort to allay any suspicions on the mother’s part that something was dreadfully wrong.

Once out of sight I ran as fast as he could to the upper deck, heading for Doctor Carlisle’s cabin. Bursting into the passageway I nearly collided with the older nurse.

“There’s something wrong with the Bradshaw baby!” I was out of breath after the run up the midship’s stairway. The nurse looked at me in disbelief, her face showing distaste at my obvious panic.

“That’s impossible, I only saw her just an hour ago,” she replied in a patronizing tone, and she turned to walk away.

I took her firmly by the arm, stopping any further movement on her part and looked directly into her face. “That baby is on the port side under the midship’s stairway, if you don’t get down there right now you will have to take the consequences for the rest of your life. There are no signs of life on her face”

The nurse’s face changed to a look of concern, and I reinforced what had to be done. “Get that baby down to the hospital and I’ll get the doctor.”

It was awhile before I found the doctor, he was in the radio room, his only link for advice from the outside world. but all the experience he had gained as an army medic may not hold him in good stead with the treatment of these babies.

His usual dead pan face grimaced as I imparted the bad news, and for once he removed the cigarette holder without speaking.

It seemed an age before they arrived at the dispensary, the door was open and Doreen Bradshaw was sitting on the only chair, a look of confusion on her face. Doctor Carlisle was about to call out to the older nurse who was in the hospital ward, when the younger nurse appeared in the alleyway, a look of urgency on her face.

The doctor asked her to stay with Mrs. Bradshaw and gestured for me to follow him into the hospital.

The older nurse turned her head as they entered, her ashen face and the look of despair in her eyes spoke volumes. She looked directly at me as though to apologize for her earlier reaction, and I knew that she would never dispute anyone’s opinion again without first verifying it.

Medical jargon ensued which made no sense to me, but in any case, my concentration was on the baby girl, so small and still, the size of her small body dwarfed by the man-size hospital bed.

I had seen men die during the war, but this was something different, and I was finding it difficult to believe what I was witnessing. The tone of the conversation between the doctor and nurse appeared monotonic and hollow, accentuated by the reverberation in the empty steel room.

The doctor moved towards the door and called out to the young nurse in the dispensary to bring Mrs. Bradshaw in. I abruptly stood up and instinctively moved towards the door but the doctor gestured for me to stay. Looking across towards the bed again, I just caught sight of the baby’s face being covered with a sheet.

It seemed an age before the door was pushed open and Doreen Bradshaw entered, closely followed by the young nurse. Her face was still passive, but as she looked between the doctor and nurse at the form lying covered on the bed the full realization of the situation hit her and her face changed to one of terror. Screaming, she ran forward falling to her knees alongside the bed, pulling at the sheet that covered her baby’s face.

Doctor Carlisle moved out of the way so quickly, it took me by surprise, his teeth were clenched so tightly on his cigarette holder, I thought it would snap at any moment. He was under immense pressure now, and would be confronted by the other mothers with sick children.

The next few minutes before Mrs. Bradshaw was taken sobbing back to the dispensary were agonizing. She would have to be taken back to her cabin, via the open deck as there was no direct access to the midship cabins, other than by the open stairway.

I was not feeling too good myself now, with a dull ache in my chest, no doubt from the tension that had built up, and my heart had sunk down into my boots refusing to budge. Doctor Carlisle’s voice galvanized me back to reality.

“I’m sorry you had this thrust upon you Bonner, but there are things to do now. Lift the safety rail on the bed and when I leave, I want you to lock up the hospital and go to see Gary Somers the lamp trimmer, he’ll know what to do. The child will have to be buried at sea tomorrow.”

After watching the doctor leave, I quietly closed the steel door and inserted the key into the lock, but I could not find the courage to turn the key.

My mind pictured the child lying there and the urge not to leave her locked-up and alone was powerful. Opening the door again I fully expected her to have moved, but that was not the case. Quickly turning the key in the lock, along with the dispensary door which had been left open, I made way forward to the foscule head where the lamp trimmer had his work room next to the paint locker.

Walking along the passenger deck it was obvious by the eyes following me that word had got around and I was approached by Megan Richardson the mother of a sick boy, also about seven or eight months old.

“Is it true that the Bradshaw baby has died?”

“Yes,” Will replied, which was followed by a barrage of questions.

“Look Mrs. Richardson, I’m not a medical person, but I’m sure Doctor Carlisle will be talking to you, I will take you to see him right now, if you want.”

After leaving her with the doctor I made my way forward again, but before I descended the stairway, the lamp trimmer was heading towards me across the deck.

“How are you Lampy?” which was everyone’s nick name for him.

“Okay Will, did you want to see me?”

“Have you heard about the Bradshaw baby? Doc. Carlisle asked me to let you know.”

“Yes, I’ve heard, it’s terrible news, I shall have to get some materials together. Would you open the hospital, just after dark this evening, and I’ll see you there?”

I watched as I made my way along the passenger deck, apart from any further instruction from the doctor there was nothing more I could do, so I made my way to the crew’s dining-room to scrounge a cup of coffee. Just about everybody plied me with questions, but before very long I’d had enough, and feeling tired, retired to my bunk to try to sleep.

It was dusk as I made my way down to the hospital. The night was warm and still, with the moon high overhead. Lampy had just arrived at the dispensary and a deck boy was depositing some canvas in the shadowy alleyway. He turned to the boy. “Go forward and tell the bosun I need to see him in the hospital, you can then go off duty, but make sure you pass the message to him personally.” I could hear the boy clambering up the steel stairway as I opened the door to the hospital and they both went inside.

The electric lighting was poor and it flickered sporadically, the symptom of an old electrical generator, giving the room an eerie atmosphere. Things were bad enough without this, I was thinking. The two men stood on either side of the bed looking down at the small still form, and then looked up at each other without speaking. The lamp trimmer broke the silence and speaking in a nervous whisper, “I’ve never prepared a child for burial at sea before and I’m a bit nervous about doing it.”

“That makes two of us.”

Lampy’s hands reached down to remove the sheet and I could see that they were trembling and right at the last moment he withdrew and started to measure up without removing it. This last action prompted me to pull myself together and taking Lampy by the arm to stop him from carrying on, he quickly removed the sheet. She was still dressed in her white cotton nightgown, a beautiful little girl, and Lampy was visibly shaken at the sight.

“She looks just like an angel,” and bending down he took a large lead weight from his bag and placed it a couple of inches away from her tiny white feet, proceeding to measure up for cutting the canvas. The men’s minds became occupied with their task as the weight was sewn in and the canvas prepared for stitching, and when they were finally ready Lampy looked across at me, hesitating before he spoke.

“What’s the matter?”

“You’ll have to pick her up while I position the canvas.”

How stupid of me, it should have been obvious to me from the beginning, but in an odd sort of way he felt relieved at not having to think about the possibility during the proceedings. I supported her head and picked up her stiff little body, the feeling of which discounted any thoughts in my mind that she would suddenly awaken. Lampy began nervously to sew up the canvas and with each stitch the shape took on the form of a cocoon.

The silence was abruptly shattered by heavy footsteps, followed by a loud knocking on the door. “That will be the bosun,” Lampy remarked.

“Come in bosun,” he called out. A few moments of silence followed.

“No, you come out here Lampy,” was the reply, a hesitant tone in his voice.

“You’ll have to come in and verify that everything is okay, Lampy countered. “We can’t finish the job until you do.” A further period of silence ensued.

“Just tell me that everything is okay, I’ll accept your word for it.”

Lampy looked across the bed at me. “Go and fetch him in,” he whispered.

I opened the door to see Shaun McRae standing well back in the shadows, but I could see that he was visibly shaking. At first, I thought he had been drinking, but began to realize that he was just scared.

“Are you alright bosun, you’re not sick, are you?”

“I knew from the start that this voyage was doomed and now we’ve been cursed,” he said, breaking into a babble of Gaelic. I opened the door wide.

“You know what the rules are, you have to verify that you have seen the Bradshaw baby before he closes up the canvas.”

By this time the bosun had turned his back to the door, refusing to look beyond me into the hospital ward. “I’m not going in,” he said, shaking his head vigorously.

“I’ll soon remedy that. I will carry the body out here for you to see.”

Making my way across the ward, I could hear the bosun scrambling his way past the dispensary, and in his haste to get away, tripped over the doorstep at the end of the alleyway, falling out onto the steel deck. What appeared to be a string of Gaelic oaths followed as he painfully limped his way up the open stairway to the upper deck. I looked across at Lampy and we both smiled.

“They are very superstitious people in the bosun’s part of the world,” Lampy explained, but I could not foresee that I would use this particular episode against the bosun at a critical time in the future. Read my story about "Smithy" in Memorable Moments.

With the work now finished I breathed a sigh of relief as I locked the door behind me. The burial would take place the following morning at 10.00 a.m. Lampy left to prepare the remaining items, including the board from which the little mite would be deposited into the sea.

After a troubled sleep I made my way down to the dispensary for early surgery, but as if to reinforce the general depressing atmosphere, only a couple of the crew attended. Doc. Carlisle asked me to come to a meeting in his cabin after the funeral, apparently the two nurses would also be there.

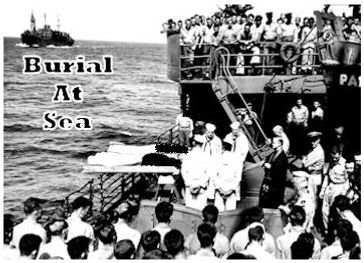

I sat alone in my cabin to await the time for the funeral, which was signaled by a sudden stop in the engine vibration and the ship began to slow down. I leaned against the railing overlooking the deck. The ship by now, was just drifting in a remarkably calm sea, and even though just about everybody had crammed into the area, all that could be heard was the gentle lapping of the water against the side of the ship.

The rules had been abandoned for this brief time, and the uniforms of the crew were scattered amongst the passengers. The immediate area around the flag covered board, which could be seen protruding over the ship’s rail was clear, except for the ship’s officers and Mrs. Bradshaw who had started to cry again. She was being comforted by two of the women.

Stepping forward the captain started the service, but throughout the whole proceedings my eyes were transfixed on that little shape under the cloth, my mind penetrating the canvas, seeing the baby’s face. A sudden movement broke into my thoughts as the two men at the rear of the board lifted it to a 45 degree angle, and the miniature, canvassed form, catapulted from under the cover into the open air, falling rapidly with a faint splash into the sea, followed by a few bubbles as it descended into the deep depths.

I turned away and headed towards the Doc’s cabin, I had a terrible sinking feeling in my stomach, a result of the previous traumatic twenty-four hours, and I desperately wanted to try and put the immediate past behind me. The decks were still deserted as I headed for my cabin, but a lone figure sat outside the paint locker looking out to sea. It was Lampy and the two men exchanged nods, but no words were spoken. I heard the engine burst into life, indicating that this particular episode was now over.

The meeting after the funeral amounted to a simple plan of action by Doc. Carlisle. He had spent quite a bit of time talking to other doctors by radio, and a decision had been made to prescribe a drug to the other babies that had been developed and used extensively during the war, but only for treating adults, not children, especially babies so young as these. But he had not been able to find anyone who could help him with the dosage and possible side effects consequently, the dosage had been arrived at by a consensus of opinions from several sources.

It was decided that of the three babies that were sick, the two nurses would look after one baby each, and me the third, a boy whose mother was Megan Richardson. The mothers would nurse their children under instruction from the doctor, but it was the duty of the nurses, and myself, to see that the drug was administered as prescribed, and to keep an eye on things from hour to hour.

Arriving at Megan Richardson’s cabin I looked down at the boy and I could see immediately that even though he looked sick, he appeared in far better shape than the Bradshaw baby, in fact robust in comparison.

I became aware that Mrs. Richardson was looking intently at me in anticipation of a comment. She was a very small woman, with blonde hair and large blue eyes that looked tired. As with the other women, the past few days had been a nightmare for her and she no doubt knew that it would be awhile before they could hopefully relax.

“What do you think Mr. Bonner?”

“Just call me Will, I’ll tell you the truth as I see it.” Those large eyes were fixed on his face as she awaited his answer. “You know that I saw the Bradshaw baby?”

“Yes.”

“Well, this little fellow looks like a weight lifter in comparison.” A glimmer of relief came over her face and I looked down at the baby again. “What’s his name?”

“Andrew.”

I reached out and held the baby’s hand. “Andrew, we’re going to stick to you like glue until we reach Melbourne, and get you in shape to see your Dad.”

The boy looked up at me and I could see that he had the same strong features as his mother. After giving the first dose of medicine, they both sat in the cramped cabin and waited to make sure that Andrew didn’t reject it.

Megan Richardson was a Welsh girl, who had joined the Women's’ Auxiliary Air Force (W.A.A.F.) and was assigned to the crash wagons that would meet the aircraft returning from bombing raids over Germany, to remove the dead and wounded.

It was on one such occasion that she met her Australian husband David, the pilot of a plane that had been badly damaged from anti-aircraft attack, but which had limped back home across the North Sea, finally crash-landing at the air force base. The plane caught fire and the emergency crew had just managed to get David out before it began to explode. He was hospitalized where Megan visited him, and they were eventually married in England before David returned to Australia. Andrew was born after his father had left, so their arrival in Melbourne was going to be a memorable one.

I now knew that Megan Richardson was a very capable woman which would make my job easy. It would still be vital however, to see the medicine administered on a four-hourly basis and report to Doc. Carlisle so the next few days were going to be demanding. Appearing at Megan’s cabin door every four hours to verify that the dosage had been accepted by Andrew, and wait to make certain that he didn’t vomit it up, was tiring, with only the chance for an occasional couple of hours sleep. But on the fourth day everyone’s effort seemed to be paying off, and all the babies started to show signs of improvement. Andrew would smile as I picked him up for his medicine.

Times of crisis now appeared to be disappearing, and the depressing atmosphere that had descended on all aboard, with the death of the Bradshaw baby, was now visibly dissipating. It was just routine until the Australian landfall was sighted. The babies were well and truly out of danger, but still weak and in need of nourishment.

Doc. Carlisle was now the man of the moment - having averted the worst possibilities.

The ship stayed in Perth only one day with the next stop Adelaide. Doreen Bradshaw was to disembark here and all the family came aboard to see Doc. Carlisle. The whole affair was vividly brought to the forefront of my mind again, and to make matters worse, the father, knowing that I was probably the last person to see his daughter before the funeral, began asking me about her. I could feel that ache in my chest again as I pictured the little girl’s face, and Lampy’s words, “she looks just like an angel.” and struggled to take control of my emotions.

“I helped to get her ready,” I said, choking on my words “and the lamp trimmer said she looked like a little angel.”

Tears started to run down the young man’s face. “I’ll use those words at the church service we’ll be having, now that my wife is here.” I could stand the tension no longer, and moved to the ship’s rail between the lifeboats to let my feelings subside.

A Footnote to my story

When we arrived in Melbourne. Megan Richardson's husband was waiting to collect them and I was introduced.

Before my ship left Australia for its journey back to England I was invited to a family and friends get together, at the Richardson's, to welcome Megan and the baby Andrew.

What transpired remains vividly in my memory to this day.

When I arrived to a gathering of some 30/40 people, and they all started clapping and cheering, which to use a phrase literally blew me off my feet. They had obviously been told about the outbreak amongst the babies on the ship. The baby was in a crib next to his grandparents. They all cleared a way for me to go over. I leaned over and the baby smiled, which brought forth another round of applause and cheering. " Look Andrew knows Will"

My story does not end there. After WW2 I married my wife Dorothy, and the Richardson's sponsored us resulting in our 20 year stay in Australia.